In 2016 we were invited to be artists-in residence with QuProcs (Quantum Probes for Quantum Systems) a joint research project between a number of international labs.

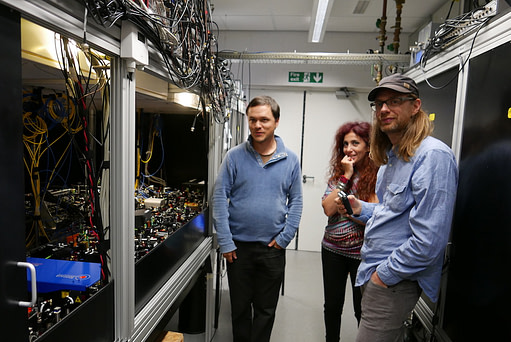

We made research trips to three of these: the Clarendon Laboratory at Oxford University, the Computational and Quantum Optics Group at Strathclyde University in Scotland and the Quantum Lab at University of Turku in Helsinki.

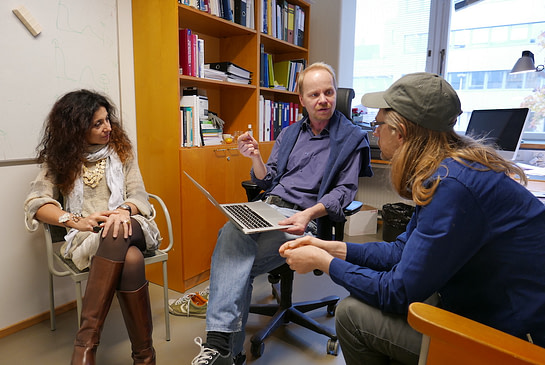

Supported by Professor Sabrina Maniscalco we arranged meetings with the teams at each of the labs, and undertook our own research to get to grips with the whys and hows of what the scientists were doing.

It is always quite overwhelming and exhausting jumping in the deep end in this way, spending an intensive period taking on lots of new information that you don’t fully comprehend, but we have found it is actually key to how we work. Engaging directly with the scientists rather than learning from the written page enables you to get the bigger picture, experience how the science functions in the lab and gives opportunities to delve into specific areas of interest and build up relationships with the scientists. All of this becomes integral to our process of making an artwork when engaging with scientific settings.

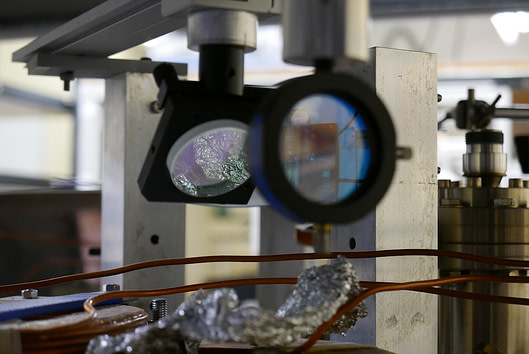

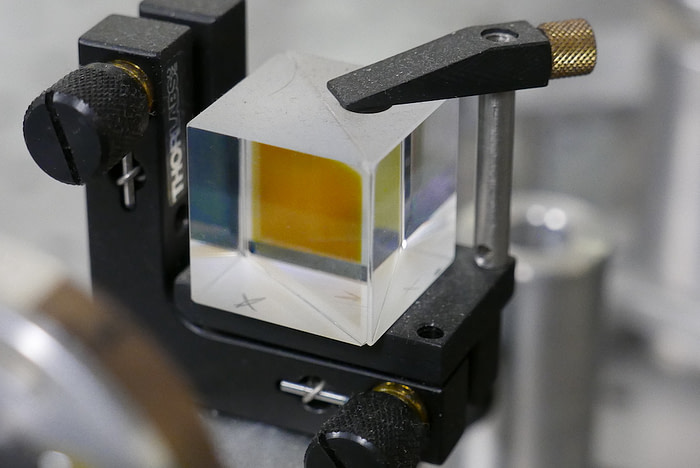

One of the key experiments carried out by QuProcs at Strathclyde University involves attempting to look at individual atoms trapped with light to understand better the problems of solid state physics. By using lasers the scientists trap atoms in an ‘optical lattice’ just like the crystal in a semiconductor, the lattice mimics atoms in real world materials. This process allows the quantum behaviour of atoms to be studied. Atom sources, which are metal in atomic form, are heated up to a vapour, and then cooled and pushed, as a beam, through stages of cooling, to get to very low temperatures. The low temperatures enable the scientists to see the atoms isolated to observe their quantum behaviour.

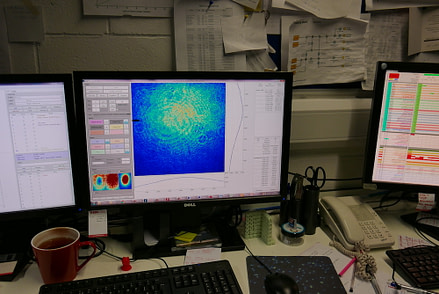

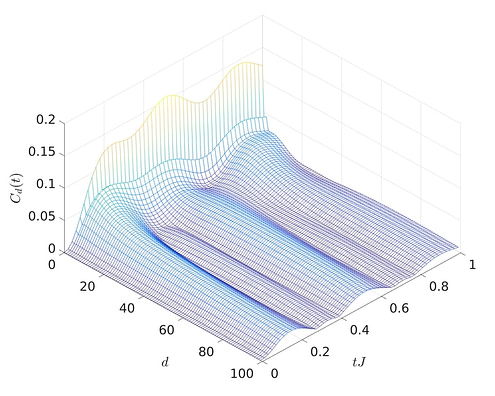

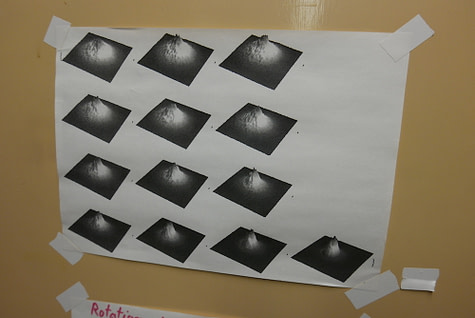

The scientists described the experiment as starting with a system which is settled, and then disturbing it, shaking it, removing one particle in the middle, then taking images in time intervals which reveal something about the quantum behaviour of particles.

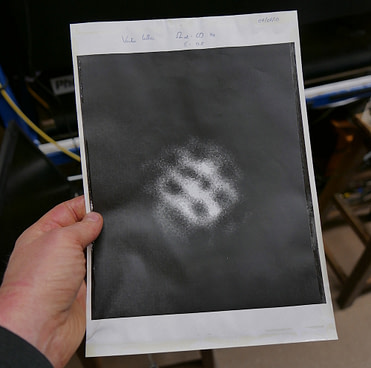

We were interested to hear the researchers speaking about different kinds of ‘image capturing’. They described two types of image: Fluorescing the image, which consists of collecting the photons emitted by the atoms, and the data is the matrix with intensity. The other technique, absorption imaging, is the inverse, where you image the absence of light. You take two pictures, one with the atoms and one where you shine light onto the atoms. You collect what comes through and in effect you get a picture of atom shadows.

One of the key bits of learning from these conversations and our time in the QuProcs labs was the principle that complexity arises from the build-up of particles when studying their individual interactions on a microscopic scale. That new unpredictable phenomena emerge (Sabrina Maniscalc, Oxford).

As Andrew Daley told us ‘a lot of the most exciting discoveries with physics have not been discoveries from suddenly seeing that something is fundamentally different about the microscopic, they were things about how particles behave when there’s many of them – their collective behaviour – a behaviour that you couldn’t predict even if you knew very well how things behave microscopically.’

The first person to describe this on a philosophical level was physicist Philip Anderson, in his editorial in Popular Mechanics, More Is Different: Broken symmetry and the nature of the hierarchical structure of science, (4 Aug 1972, Vol 177, Issue 4047 https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.177.4047.393)

Andrew goes on to explain ..when we start investigating what was happening in particular condensed matter, the physics of electrons and solids, we started to discover that even if you could write down a microscopic model for how nature in principle worked , it did not mean that you would immediately understand all the properties that came out of that.

As soon as you started to do physics on a scale where you had more particles involved, it was not enough to know these microscopic models, it was almost like a new science completely unto itself to understand what was happening.

In the past we have spent time in science laboratories with very large fields of interest. For this project it was great to gain insight into a more specific area of research. It enabled us to carry out in-depth research in the area and get a thorough understanding of the science being carried out, with a clear overview of the experiments, simulations and theories being explored.

When starting our residency some of the scientists were initially unsure about what we might want from them, this was partly due to none of the labs having previously had artists visiting. At one lab a scientist opened up to us at a dinner saying he hadn’t been interested in meeting the visiting artists, but that after we had spent some time with him talking about his work he found it really enjoyable and beneficial to him, helping him to consider his work in a new way.

Following two days spent at the Turku lab in Finland discussing with the theorists in groups, what they do and the fundamentals of their work, Sabrina said that several scientists had told her they really enjoyed talking to us in this way as they don’t get to talk to each other like that normally; for them it opened up new ways of engaging with each other. Receiving this feedback from scientists during our residencies helps us reflect upon our role as artists and to get a better understanding of what we can bring to science settings as well as what we can take away to help us develop new work and concepts.

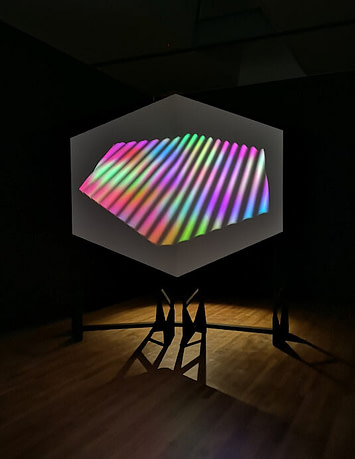

After the initial research trips and the independent research we carried out we narrowed our focus upon the mathematical simulations produced at the Strathclyde lab by Anton Buyskikh. Anton was kind enough to send us files, images and data to further our research and experiments. We then set to work developing a computer generated animation with mathematical quantum system simulations as a starting point, considering what they represent and how the language of science represents it.

The residency resulted in the creation of a new moving image work Parting the Waves, you can read more about this here.